In 1978, members of northern California’s Hoopa Valley Tribe applied for a community radio station license. The application was not routine; the outcome was not certain.

The first Native American licenses hadn’t been granted until 1972, and only two native-owned stations were currently on air. The tribe had previously applied for a 10-watt station but had been denied, as 10-watt licenses were no longer being issued.

In 1978, however, new full-power, non-commercial, educational licenses were being made available specifically for women and minority applicants, a counter to the white, male dominated radio band.

Ninety-eight tribes applied; fourteen applicants were accepted. The Hoopa Valley Tribe was one of those applicants; and, on December 16, 1980, KIDE went on air, becoming California’s first tribally owned and operated station.

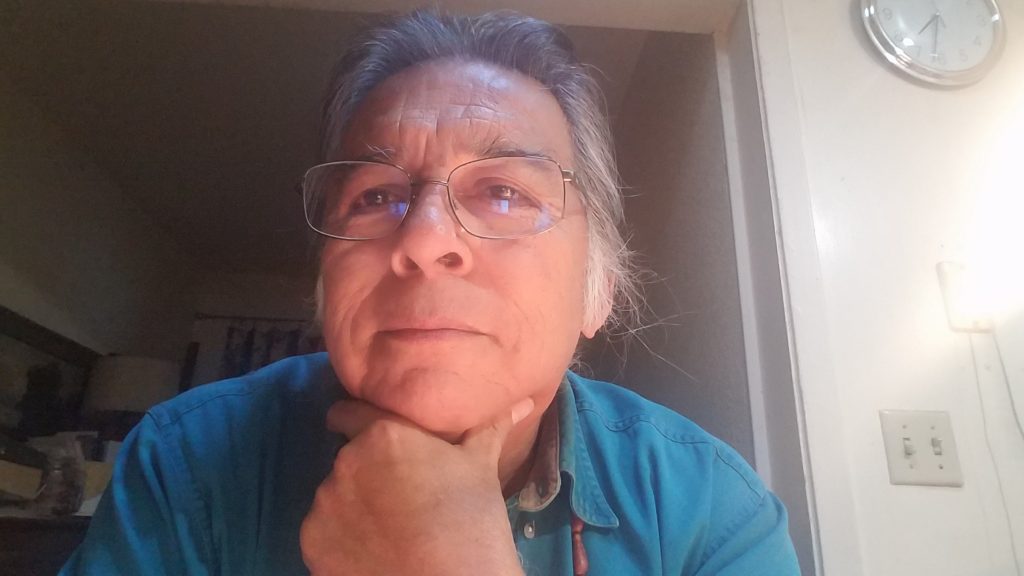

“We built the plane on takeoff,” says Joseph Orozco, long-time Station Manager and current Lead Producer/Mentor. “I took charge because I saw the value of this medium, and…the community liked it because it was ours. It belonged to the Hoopa Valley Tribe.”

KIDE now celebrates its 40th Anniversary.

Programming for a Sovereign Nation

“There’s this whole consensus type of mentality that we have to go back to.”

The Hoopa Valley Nation is—and always has been—a sovereign nation. One of the few tribes never forced out of their home communities, the people live on ancestral land. In 1864, this sovereignty was acknowledged by the Federal government. In 1988, the tribe successfully petitioned to by-pass supervision by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and consequently receives federal funds directly from Congress.

“We are,” explains Orozco, “a self-governing tribe,” and KIDE has consistently worked to expand transparency in governmental and social concerns.

Tribal Council Meetings are broadcast live; and, three days a week, the Tribal

Chairman hosts a live call-in show addressing the Covid-19 pandemic. Tribal Council candidates and regional government office candidates are offered airtime. Candidate forums are broadcast live and then rebroadcast twice. In the days before elections, says Orozco, “You…see people walking down the streets with their earplugs.”

As Lead Producer/Mentor, Orozco hopes to replace—or revise—the format of the quarterly, open forum Hoopa Tribal General Meetings with a year-round series of individual departmental reports, sessions that would allow for more questions and longer answers. “Their operations touch the community,” Orozco says, “so why not share that information.”

Programming has also supported discussion of educational issues and community health. Your School on the Air featured live interviews with employees of the local Unified School District and later expanded to include the local community college Hoopa Branch campus. A community health program, hosted by a lead nurse from the Hoopa Tribe’s K’imaw Medical Center, occasionally featured Orozco as a guest.

“He invited me to sit in but he didn’t tell me what the topic was,” Orozco recalls. “He wanted me to respond like I was a listener…We got kind of silly sometimes, but…he felt that, when people were able to laugh at the information, they actually learn it better.”

On some programs, topics—like sex education—became heated or

sensitive—Orozco particularly remembers the compassionate handling of a discussion of domestic abuse—; and scheduling is kept flexible, allowing essential discussions to run beyond their designated time.

Programming for a Native American Community

“We’ve always had trouble with communication. The news would go as fast as the rivers flow.”

In KIDE’s early years, Orozco looked to existing community radio stations for

operational ideas. Soon, however, Orozco says he realized that “the American model of radio does not fit Indian communities. We have a completely different frame of mind.” And, so, he asked, “What is that frame of mind and how do we build a radio station to address that?”

An inland tribe, Hoopa communities run along the Trinity River in a valley

surrounded by mountains that both shelter and separate. While neighboring coastal tribes, by the 1800’s, were trading with Russians, the Hoopa people weren’t reached by non-native people until 1850.

Further, although the tribe has been self-governing since 1988, Orozco explains, “we still had to follow the guidelines of Congress as…dictated to the Department of the Interior (formerly the War Department),…[and] the Bureau of Indian Affairs never funded radio stations or newspaper operations.”

This history still shapes lives today. “We live in a small, rural…community where everybody knows everybody by their voice,” Orozco continues. “They are very shy about asking a question…Where did that come from? It came from…colonization. It’s an element of this whole change of life that we went through, genocide. We were beaten down; we were told that we couldn’t speak our language….We had supervisors at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, who, if there was a dispute…would come up with a solution….It’s a figment of that whole socialization that was crammed down our throats.”

One resolution, Orozco found, was to redesign the call-in show. First, the station arranged for an operator to relay questions anonymously to the show’s host. Then, the station created a special Gmail account and offered a

guarantee: We’ll post your question but not your name.

This new approach holds promise. Orozco tells a story about how, just hours after making a public service announcement about the system, he found a note taped to his door asking about the safety of the covid-19 vaccine. He addressed the question that day on his Production Post, directing the listener to reliable sources, and suggested that the station’s Covid-19 Update program cover the issue in further detail. Says Orozco, “There are still people who doubt, suspect government control. This needs to be talked about….People…are starting to use us as a way to get more information….I think the question I found on my door is an extension of that, of us reaching out to the community.”

What Lies Ahead

“If you want to learn from your mistakes, don’t repeat them. Do something different.”

KIDE begins it fifth decade stronger than ever—this year the Tribal Council

increased its financial support to cover the salary of one worker, freeing up money from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to hire one more worker. But the station is also preparing for change.

Orozco, who has been with KIDE since 1980 and has served as Station Manager since 1988, stepped aside from that position in 2020. In these decades, Orozco has strengthened the station, Native American media, and community radio. An early advocate of Pacifica affiliation, KIDE is also active in the National Federation of Community Broadcasters and Native American radio network Native Voice One. His successor has not yet been named.

In his new role as Lead Producer/Mentor, Orozco hopes to find ways to connect a younger generation to the station. Community demographics are changing. Gender roles are shifting; more single women head households. Smart phones and social media have challenged radio.

Says Orozco, “We need younger voices and younger opinions because our future depends upon the work and tenacity of younger people…. We don’t need the youth of today to address the problems that we were trying to solve yesterday. We need them to make a new paradigm for their future….This is how you get out of the box; you take one side off and let some more air in here.”

And, Orozco believes, community radio is still the best way to find those solutions. “People keep thinking that cell phones, the internet is all you need, when actually all you really need is a newspaper and a radio station. We’re the foundations of communications in the world.”

Anniversary Celebrations

“Congratulations and kudos”

Traditionally this 40th Anniversary would have been celebrated with a party. Covid, however, has meant the milestone was marked with dedications. Local stations, national media organizations recorded messages in recognition of the station’s historic significance and endurance.

Looking ahead, Orozco says he will be satisfied “as long as people continue to use the station as a tool for the community and its resources are serving the community.”

KIDE’s website notes that K’ide is a Hupa word for an antler taken off the deer and used as a tool or for decoration. KIDE has been “a tool for the community since 1980.”

Photos of KIDE satellite and of Joseph Orozco courtesy of Joseph Orozco.