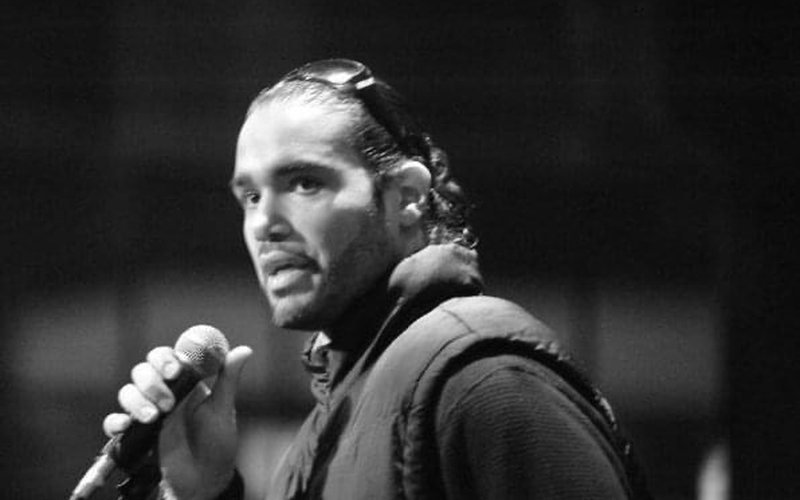

Diane Reinhardt spoke with Jose Gutierrez Jr. about his service on the Pacifica National Board on October 1st. Since then we have learned of Jose’s passing from COVID-19 complications on November 5th, just a month later.

Diane’s article talks about Jose’s vision for Pacifica, the meaning of radio, and the power he has derived from his family. We are proud that Jose served as an affiliate representative for the Pacifica Nationa Board, and we share his vision with you now, as tribute.

“Jose’s death is a terrible loss for community radio. He had leadership qualities and was part of the younger generation giving continutiy to our field.” –Ursula Ruedenberg, Pacifica Affiliate Network Manager.

In 2019, when Jose Gutierrez, Jr. was first elected as Affiliate Representative to the Pacifica National Board, the 42-year-old KAOS programmer and producer already had 30 years experience in public radio. Aware of Pacifica since the mid-90’s, he had long respected the organization’s stature, its integrity and its reputation for producing quality programming. But, more recently, he had heard that the organization was struggling.

“I was given some insight into the condition of Pacifica, a questionable deterioration of some of [its] structures,” Gutierrez recalls. “There was a tone of hopelessness and disappointment for people associated with Pacifica and public radio in general about Pacifica. That concerned me. You can’t do that with organizations like Pacifica; that’s disaster.”

Becoming an Affiliate Representative, Gutierrez hoped, would permit him to learn what was at the root of the problems and to figure out how he could help.

The plan worked; and, now, after two years of service, Gutierrez confirms, “I have an agenda, not for me but it’s an agenda for making the stations, making the network, relevant again.”

Relevancy and Self-Assessment

“Radio,” Gutierrez says, “is still the live link in society;” but, he continues, “we’re in a morphing world and we’re almost irrelevant to the new generation of people who don’t need to turn on the tuner, they don’t need to go on the dial and listen, they have streaming services to offer everything and more than a radio station does.”

These are challenges that plague all radio—public, community, commercial–, but Gutierrez fears that Pacifica is peculiarly hampered by what he sees as a lagging response, a combination of institutional history and habit that impede potential.

“It’s very upsetting because it’s not necessary to watch the dissolution of great organizations. I don’t have hopelessness but I can sense it in others,” Gutierrez observes. “They almost give up like, ‘no one cares about what I’m doing….I’m not relevant, no one cares about what I have to say.’ [But] it’s not true. It takes more work from you that you may not be willing to put in. And you’re tired. This is where the extra needs to be exerted.”

And that first extra step, Gutierrez says, must be self-examination. “You have to help people understand why they should care.”

Citing Osho, a teacher whose work he studies, Gutierrez explains, “When a child’s in the classroom and a lesson is being taught and the child’s looking at the bird that’s flying outside, you don’t scold the child for looking at the bird. You examine why your lesson can’t compete. What is the person in authority, the person in a position to lead the classroom, what are you in a position to do?”

Gaining the Support of Younger Generations

One initiative that Gutierrez believes must be pursued is engaging young people.

Now 44 years old, Gutierrez notes that he may be the youngest person on the Board.

“That doesn’t leave much promise for me to have a great outlook for Pacifica if the people running it are from one generation or multiple older generations, and there’s nobody being prepared to receive the baton….We have too many traditionalists and so many elders in radio that are kind of stuck in their ways….But this is not going to continue to exist in the way you’re doing it….We’re going to have to pass this on effectively, and until that begins to happen, we’re going to have this chasm.”

In response, Gutierrez proposes establishing a mentoring program, one “that will recruit and retain the next generation of broadcasters, to utilize emerging technology, social media, with the mentoring program to establish some leadership of another generation.” He is here, he says, “to pass the baton.”

Expanded Fund Raising

New program development and expanded outreach, Gutierrez knows, will require simultaneously addressing Pacifica’s financial instability. The network, founded in 1946 and renown throughout the twentieth century as a towering alternative to mainstream media, now struggles with debt

“I don’t want to use politically correct words,” Gutierrez begins, “because I don’t think they fit….Some of the debt and some of the financial issues that a network like this is in, it’s just really horrible….It’s really squandering an opportunity that needs to be addressed…because right now I don’t know who would want to take over.”

And, here again, Gutierrez fears engrained practices will impede change.

“There’s an adverse disposition to money in the Pacifica culture, in the public radio culture….I think Pacifica has a potential to generate funds to help address some of the challenges it’s facing. I think that it is so critical to adjust our—not to become a commercial network—but to become…finance sophisticated and generate underwriting and development campaigns….We have these big market stations. We need to have something that competes.”

Further, Gutierrez maintains, underwriting campaigns “make us closer to the communities we’re in, especially if it’s local underwriting. It’s connecting with organizations and business in your communities. It’s fundamental stuff, and it’s not as prevalent as I would hope.”

These changes, he says, are no longer a matter of preference or principle. “It’s not what we want anymore. It’s become a necessity because of a failure to see what’s coming. These are the costs for lack of vision; these are the costs for under-preparation and mismanagement, and we have to make up the costs.”

Hip-Hop Culture: Identity and Philosophy

Gutierrez attributes his strong sense of civic engagement to his upbringing, to the influences of both family and hip-hop culture.

Raised by a single mother—she was only 16 when he was born—, Gutierrez, beyond homelessness and poverty, grew up in a family enriched by love, pride, a sense of purpose and high expectation.

“Everything we do is service in my family….principles and standards that were expected of us by my mother….Being educated was a demand. Putting in extra effort was a demand. We were taught that we had to be performers in the classroom, And this goes back to…racism and how it works….You’re going to have to do extra just to be even with the general perception and social expectations of you. You know, I fit the profile…. If I’m on tv on channel 5 or the 5 o’clock news for a crime, the only people who will be surprised are the people who know me personally because otherwise I fit a profile.”

In his childhood, Gutierrez’s mother introduced him to the emerging 1980’s dance culture and to the founding principles of hip-hop: peace, love, unity, having fun and gaining knowledge.

“Identity,” he explains, “is a question mark for a lot of children of color….What hip-hop did for us is let us know unquestionably that we had a place….For us it was a life….It didn’t make us compromise our identities and our values or who we are….And why did it do that? Because hip-hop is the culture of the outcast,,,,the culture of those who have been left behind and created out of what’s left….It gave us inspiration to create something out of very little, something out of nothing.”

Then, at age 10, Gutierrez discovered the power of community radio.

One afternoon, at home in Olympia, Washington, mowing his lawn, he tuned into KAOS and heard for the first time hip-hop radio host Nancy G. She didn’t just play music; she knew the performers, the intricacies and history of the genre, and, most startling of all, she was local. After a little bit of research, Gutierrez discovered that KAOS offered training; and, by 1989, at age 12, he had his first show, becoming full-time in 1993. His first program—Live from I-5—eventually morphed into The Weekend Rap and still airs weekly on KAOS.

Tune in on any Sunday night, and you’ll hear a philosophy in the playlist.

Borrowing a line from KRS-One, Gutierrez explains, “’Rap is something you do; hip-hop is something you live.’ Hip-hop is a culture; rap is the music. When you hear hip-hop, when you’re part of hip-hop, it’s a bigger cultural dynamic.”

Something of a traditionalist—he believes “there’s no potential for a learnable and applicable future without studying origins and foundations”—and sensitive to the more materialist and violent trend of contemporary rap—a trend he fears “often has people fit the profile that I had to try to avoid which lands people in graveyards, prisons, difficult life situations–,” Gutierrez’s playlist balances old and new.

Verbal dexterity and originality are, though, always at the core of the presentation, an element central to the culture’s founding.

“Hip-hop,” Gutierrez says, “was born as an alternative to violence….Writing is a tool for competitive banter, a tool for building confidence.”

Hip-hop, he explains, “creates its own version of American English, not only using dialect and [original] terminology but creating them in a culture that’s not heathen but outcast. It comes from a group of people who have been historically discriminated against, historically left behind, and at the same time championed, adored and reviled all simultaneously.”

Recalling centuries of segregation, decades during which celebrated jazz performers couldn’t “get a meal in the same venue they were performing in” and the parallel long history of musical innovation being “manipulated out of the hands of black people or…left in the hands of other captains of industry,” Gutierrez praises “the sense of identity and pride…that comes through in the language.”

For KAOS: Essential Local, Community Radio

Gutierrez’s long experience at KAOS informs his sensitivity to the challenges facing community radio nationwide, challenges that small, local stations share with the Pacifica network.

Budget cuts have eliminated key positions. The Development Director and the Training and Operations Manager have been cut, leaving the station with only one manager. As infrastructure shrinks, Gutierrez fears, expectations fall.

“These are just things that are allowed to be squandered over time….You’re watching [that squandering] happen live,” he remarks. “You’re watching the news happen live, and it’s not being reported. Do you not see this? Do you not see the iceberg, Titanic? Is nobody paying attention? Because this could just be gone; it could turn into a college station.”

It is this local experience that feeds Gutierrez’s loyalty to and insight into his work as a Pacifica Affiliate Representative.

Trusting Our Strength

Hope, for Gutierrez, lies in his certainty about the enduring significance of Pacifica.

“We present what no one else presents,” Gutierrez says. “We are often at the forefront of what is new; we play stuff immediately…We have over 200 stations affiliated with Pacifica; we have reach….We’re creative, some of the most creative people I’ve ever met come through public broadcasting or TV….Look at how many talented people there are at these stations, everywhere.”

And, he believes, the value of that work demands that the network start now to ensure that the work goes on.

“The passionate relay runner who starts the race has to pass a smooth baton,” says Gutierrez. “If we want to win, if we want to have a successful race run, I need a smooth baton pass. I’m going to run my leg of the race different than you ran yours, but we’re still doing this together, so can you pass me a smooth baton?”

Watch Jose speak about the history of south Puget Sound Hip-Hop.