Two radio hosts and a TV producer working in Maui’s community media talk about their experience of the wildfires and why giving a voice to their community is more than just a job.

I heard about the Maui wildfires like everyone else: online and through social media. What got my attention was that these wildfires seemed never-ending, and they were happening in the United States.

As a local journalist from Aligarh, a town in northern India, I think that community media and local journalists are crucial to reporting and spreading awareness about events of such magnitude. Without them, we would not get the nuanced, personal stories; without them we could never understand the complex and interlinked lives of communities and how they face tragedies, like the Maui wildfires, and how they are overcome.

So when my editor proposed that I contact a community radio station in Maui to talk to them about what it was like to live through and report on the wildfires, I immediately said yes.

On August 8th, it’ll be a year since the Maui wildfires killed more than 100 people, displaced more than 9,000 and destroyed close to 4,000 properties, according to the latest update provided by the office of Hawai’i Governor Josh Green in February this year.

The wildfires not only burnt through parts of Upcountry Maui but ravaged the historical town of Lahaina–the former capital of the Kingdom of Hawai’i, with more than 2,000 acres destroyed.

The wildfires cost the state of Hawai’i an estimated $5.5 billion in damages, according to a preliminary report by the US Fire Administration, also released this February. They stand, as the report states, as “the worst natural disaster in Hawai’i’s history” and the fifth deadliest in U.S. history.

I had the opportunity to speak with Braddah Tony, Myriam Laraway and Suzy Gastrein. All are Maui residents and all of them work as community media persons on the island.

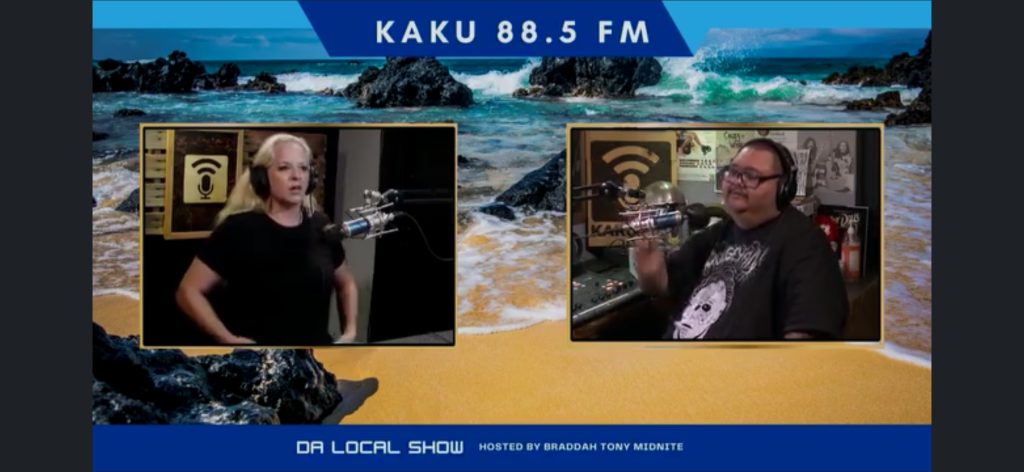

Braddah Tony (who also goes by Tony) and Myriam are radio hosts at KAKU 88.4 FM community radio that calls itself “the voice of Maui.” Both take this tag seriously. Braddah Tony is the host of ‘Da Local Show,’ where he offers a space for local Maui voices to share their stories. Myriam hosts ‘Latino Connection,’ a Spanish-language talk-show that gives Maui’s Latino community a voice.

Suzy is a TV producer at Akakū Community Media, the parent organization of KAKU. Currently, she produces short form segments for The Maui Daily Report for Akakū Channel 55. She settled in Maui–Lahaina, specifically–for good, back in 2018 and was in Lahaina during the wildfires. She shares with us her personal firsthand account.

***

Meher Ali:

What is the current situation in Lahaina, and Maui in general right now?

Myriam Laraway:

Speaking of my Latino community, it’s really hard for them. First, because of the language, of course. They’ve tried to cope in different ways, helping each other because so many of them, the people who suffered this tragedy, have no documents. So they don’t really have many options to go and get help from the government, so they try to help each other. [They get help from] different organizations here in Maui but not directly from the government like money.

And at the time of the tragedy in Maui in general, we try to help each other; we don’t hesitate and we just go right away, however we can.

Braddah Tony:

There are still a lot of local Hawaiʻians as well here—indigenous Hawaiʻians—that have trouble trying to ascertain living situations. There are certain organizations out here that protest by camping out on beaches, where they call it “fishing for housing,” where you would have to fish on the beach just in order to have a place to sleep right now.

This is due to a situation where a lot of the survivors from Lahaina, who were given access to room and board in some of the resorts and hotels here, they’re currently going through the process of being removed. And our government is trying their best right now to get as much funding and as much help to the people, but it’s a very slow process. Most times after a tragic event like this, you know, it’s a very long process that we have to go through.

Suzy Gastrein:

It’s been a very tough situation. It happened very suddenly. We couldn’t be in the loop; we couldn’t communicate with the other side of the island. This was the greatest challenge: not to have regular [information] updates as the fire was moving along. We hopefully will be more prepared, if there is a next time, because fires do happen, and they can happen again. We’re crossing our fingers.

I can confirm what Miryam and Tony have spoken about. I want to add that there has been PTSD for many of us, even those who are not close to the fire; we still feel the pain. And we’re also living in the hope of recovery, which is going to take, as Tony said, a long time. FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) and SBA (U.S. Small Business Administration) and other organizations have been on the island, trying to maneuver their way around, having to multiply their efforts in many different languages, and in a way that people would understand what’s available for help.

Housing has been an issue. People have left the island because they couldn’t get any housing or housing that was offered was far away from the community where they had spent their entire lives. And now we have to deal also with the debris removal, which is toxic and the authorities, the community leaders had a very, very hard time deciding what to do. Meanwhile, the community was observing what was done and for many of us, we thought it was too slow and hazardous. Decisions were made as leaders were confronted with something that big that hadn’t happened in a very long time in the US [and] here in Hawaiʻi.

Meher:

Can you, Myriam and Tony, talk about your work at KAKU 88.5 FM community radio and how you both involve the community in your respective shows?

Braddah Tony:

I started working here more than eight or nine years ago with my own program, kind of podcast style. The previous engineer, Shaggy Jenkins [Veteran TV and radio host and former Program Director at KAKU], who also helped get Myriam’s show up and running, basically taught me the ins and outs of engineering an entire radio station. And that’s how I got the engineering job over here.

As far as my radio show—“Da Local Show”—it’s what we call here in Hawaiʻi, a talk-story show launched in 2017. I invite as many local community members organizations; I’ve had interviews with people [about] the housing situation here on the island and the homeless situation; I’ve had interviews with artists and musicians here on the island. And basically, my show is kind of the heart of KAKU because I invite so many local citizens on the show.

Ever since the fires, I’ve had many organizations come in and talk about what’s happening, from FEMA to Red Cross to all the people that were on the ground during that time.

[Community voices matter] because first and foremost, we are a talk radio. There are a lot of shows here on the island that would invite people, but I think being a public radio station, I feel very obligated to have a show that gives a voice to the community. I’ve had a lot of interaction from people on the street saying that we’re the only people here on KAKU that have given the community their voice.

Myriam:

Well, I’ve been here since 2016. I’ve been a radio host since that year. Shaggy Jenkins gave me the opportunity to have my radio show. Since I’ve been a radio host in Mexico, [that was] for like 12 years, I wanted to do the same thing as I was doing in Mexico. Now in Maui (since 2016), I see that there is not much help out here for my Latino people. And I say, I need this. I need to connect with people. That’s why my show is called “Latino Connection.”

So I want to be the same, as Tony said, the voice for my people. And I’m for the whole Maui community; I try to connect with everyone, but also to help my Latino community, because, again, language is a big problem.

During the fires, I say, I need to do something, because they don’t speak English; they don’t have any documents, so I need to connect with local organizations. I was knocking on doors saying, “I need help. My people need help.” I didn’t know what I could do, so I tried to connect with them.

And this is a part of me, like I want to give to my community because Maui gave me a lot and I’m really grateful to live in this place. This is my second home.

Meher:

Suzy, could you talk a little bit about how you came to work at Akakū Community Media?

Suzy:

While living in the Bay Area, I had come to Maui many times on vacation and at some point after gentrification [in San Francisco] and long commutes, I decided that I needed a little more peace. And, so I came here and ended up living in Lahaina. I fell in love with Lahaina because of its unique history. [This was] six years ago.

I was interested, just like Myriam, because I had done radio in my native country (France). The first step for me was to start radio again, (that’s when I met Shaggy), not because there is a large French community here, but just because it’s always nice to share your culture wherever you go. As much as I’m learning from Hawaiʻian culture, there’s a lot that I would like to share about French culture.

I came here. I was helping with radio, but there’s also television here [at Akakū] with some classes in education. I told myself, I’ll do it, but once you get into video, you realize that it’s really time consuming, much more so than audio projects. So, though once in a while I send something to Tony, the rest of the time, I’m mostly on the TV side.

THEIR EXPERIENCE OF THE WILDFIRES AND KULEANA

Meher:

And, if you’re comfortable talking about this and if not, that’s absolutely fine: What was your experience during the wildfires? And how did you balance being both Maui residents and media persons who were covering and talking about the tragedy?

Braddah Tony:

The evening that it happened, we were asked to evacuate our residence. The area where I live on Maui, it’s not close to Lahaina; it’s Kihei [about 45 minutes away] and there were fires that affected this side as well. Nothing in the residential areas, they were more in the plain areas; the brush areas. So I evacuated and stayed at our family’s house. I wake up the next morning to find out that Lahaina is completely gone.

I had to come into work that day just to see what was going on. I felt like, again, it was my duty to intervene as a radio host and broadcast whatever was coming in from Akakū’s side. Even on that day, I had organizations that came in and we went absolutely live doing Akakū’s live stream to relay a lot of messages.

I was monitoring a lot of programming that was coming in, not only with Pacifica, but others in the media at that point. There was a lot of misinformation on social media, but a lot of good information as well let’s say from the top media news [outlets] all the way down to independent news organizations.

The Bradcast did an episode for the wildfires where they did an interview with Shaggy Jenkins, who was the original KAKU engineer here. He had a very informative episode and Shaggy really laid down a lot of what was really happening at that time.

Initially the days after [the fires], I was the only one on air that had an abundance of guests who came in to talk [like] about where to go for shelter, for food, for clothing. So yeah, I felt it was my duty to just be here and broadcast all that stuff.

Suzy:

I just want to add that when we say “it’s our duty,” there’s a term here that we use, it’s called “kuleana,” we say, “it’s our kuleana…”

Myriam:

Yes, it means “responsibility.” So, because the station is a community media, that’s what we tried to do. I mean, that was a…Tuesday. I live in the countryside, 40 or 45 minutes from Lahaina, and in that area [Kula], there were also fires. I was afraid.

And next day, same as Tony, we find out about Lahaina’s fires and everything’s gone. And I was crying, I was like, what’s gonna happen? I mean, so many things came to my mind and so devastating, I would say. So yeah, that was a hard time…

Braddah Tony:

hard time writing a show…

Myriam:

Friday, I did my show [three days after the fire] and I have no words. I don’t know what to do; what to say. I just tried to follow up with different organizations about where people can go and get food in different areas of our community in Lahaina or actually in central Maui and Upcountry. But yeah, it was a sad, sad time for us, for everyone.

Meher:

YeahI listened to a recording of your show. I mean, I don’t speak Spanish, but I could understand and you said, “I don’t have the words,” when you were talking about the tragedy. And then you observed a minute of silence.

Myriam:

Yeah, am gonna cry…

Meher:

Yeah I mean I almost cried when I was listening to you, even though I don’t speak Spanish…

Myriam:

I just was thinking about the people of Lahaina. And Suzy was in that part. And we tried to communicate with her. I texted her like, “Are you okay? Are you okay?” And I don’t get any answer so I’m like, what’s going on, I hope she’s doing good. I was afraid that people could not communicate with us and ask for food, water. We were just afraid for them and we wanted to help them but we didn’t have any way to go over there or call them or talk with them.

Braddah Tony:

It was really hard to get communications out to Lahaina at that time, so they couldn’t hear anything on the radio, nothing. So we’re here on the central side, Upcountry Maui and this is basically the central area of the island. We had communication going on, but it was a week and a half of not having communications with Lahaina.

The first real initial information was given to us by the county.

Suzy:

The thing is, with the hurricane that was here, prior to the fire [with] heavy, really strong winds, we already were pretty tired by that. And then this fire comes down.

The night it happened, power and Internet were already out. It was dark with heavy winds; the smoke was blowing the other way, so I had no way to know that something was [wrong].

It’s Myriam right here whose text surprisingly came through and made me realize that something really, really bad was happening two miles from where I live. Two miles.

There was complete Internet outage, no phone, no TV, nothing. We realized later that one solution would be to go in our car and listen to the radio. We had to rely on word-of-mouth information because we could not even get news from social media, with no connectivity.

So we created a network on the hill, where I live and work, and somebody from the mainland decided that the only way they could help us was to send group texts to about a few dozen people, and we would get the texts whenever we could. So information that we couldn’t get locally was actually going through mainland US and then back to us. And it would only get to us whenever, you know, connectivity, which was spotty, would come back. [Interviewer’s note: Suzy also added that it could take 15 hours or so for the text to reach her phone in Lahaina.]

It was extremely difficult, and being in the media, I was also feeling the kuleana, being on that side of the island, to give information about what was happening there. But this could not happen [because there was] no connectivity.

And it was just incredible [when] the morning after I, not having been able to evacuate (as more flames were reaching our south Lahaina hills), I went to the other side of the hill, and saw this image of Lahaina. You could barely see Lahaina; you could see this large gray cloud.

And of course, this image stuck in my mind knowing that just two miles from where I live, people had been struggling for their lives the night before. And I didn’t know this was happening.

So yeah, connectivity was something that was not there. The situation was very complex. And there has been misinformation, [people] blamed, and we’ve had a lot of heroes. Myriam was one of those heroes.

It’s been very difficult for a lot of us to talk about it, but we appreciate the way you’re doing it right now.

Meher

Thank you Suzy.

“PRICED OUT OF PARADISE” AND WHAT THEY LOST:

Meher:

I read about how, after the fires, many people are scared that they won’t be able to return to their homes, because of the rising cost of housing. Can you talk about this?

Braddah Tony:

The situation is that housing has been a problem even before the fires. The terminology [that is now used for Maui is] “priced out of paradise” [meaning the cost of living is causing locals to leave the place where they grew up] and that’s just for housing alone. Here in Hawaiʻi, the financial situation has gone up especially since COVID. When we came back from lockdown, a lot of taxes kept getting higher and higher, whether it be housing or shipping tax. With the fires, it is now even more difficult.

There have been a lot of families here in Hawaiʻi, on Maui that have relocated to the mainland. But a lot of survivors are [also] planning on remaining on the island, and it’s just, you know, from here on out seeing how the government can really help some of these individuals, like one of our senators or governors is trying their best right now to get housing.

Meher: And is the rising cost of housing due to tourism?

Braddah Tony: In part, yeah.

Suzy:

Having lived in San Francisco, where I witnessed gentrification, I would say there’s some type of gentrification that has happened here with people like Jeff Bezos and Oprah Winfrey buying million dollar estates. And as Tony mentioned, after COVID, a lot of techies came here to work from home and away from COVID restrictions, so this brought about a situation that did not align with us, the locals, living here and transplants. So, I would say this added to the housing problem: the high cost of homes.

Myriam:

Because of this fire, this is no more a paradise for the locals. This is outrageous: the prices, the food, the regular, everyday things; we can’t afford it anymore. And these rich people take over these domains. All these people, we live here, especially the indigenous Hawaiʻians. If they leave this place, it’s no more Hawaiʻi. So this place is gonna be over if they [the mainland wealthy Americans] take over this place. Prices are gonna be high and we’re gonna run away. So, [it won’t be] Hawaiʻi without Hawaiʻians, pretty much.

Meher:

And in Lahaina, can you give me some idea of the people who were affected the most? Were they native Hawaiʻians, were they Latinos, like I just want to understand disproportionately who has it affected the most?

Myriam:

Well, it’s a big community over there. There are a lot of hotels. So pretty much a lot of immigrants, some Filipino, it’s like a melting pot, so everyone was affected. I mean, the whole island was affected. We were crying; we were holding each other. Even though we didn’t lose houses and we didn’t lose any family members, there was a 9/11 in Maui and we were all affected.

Suzy:

I want to talk about the culture of Hawaiʻi, of Maui, because we just lost some of this as well. We lost not only hundreds of structures that represented the culture, the tradition of Lahaina and Maui, but we also lost 101 lives. And everyday, we can’t ignore that this has touched us in a very profound way. And we have to recover. It will take a long time. We know we have lost a lot.

Meher:

How long do you think it’s going to take for Lahaina and for Maui to recover or is that something that’s not even possible to gauge?

Myriam:

Like you said, that part is not my own to answer because that’s only for the people who lost family members, their house. It’s not something I can measure.

Braddah Tony:

Yeah, exactly. Again, Lahaina was the oldest historical town on the island. It was one of the first towns all the way since the whaling days to the changeover and it becoming a tourist town.

We lost a lot, we did. Certain areas of the islands, some old homes in Upcountry Kula as well, that sat there for 50 years or so, were affected. It’s gonna take some time. As Myriam said, we can’t measure the amount of time that it will take to heal this island.

WHY MAUI STILL MATTERS AND ALOHA

Meher:

I wanted to ask about how you all are doing, in terms of both coping, if you want to talk about that, and then professionally as community media persons through your work to move forward with recovery and healing? And though it’s obvious, I still want to ask: Why is it important for us to keep talking about Lahaina and Maui in general?

Braddah Tony:

Professionally, I’m doing my best to get as much information out there still to this day, because there is still a lot that’s going on over here that nobody knows about. That’s why I invite a lot of people on the show to talk about it, because I myself am not on the ground. That’s why I’d rather hear it from people that know more than I know, and that’s why I have the radio show.

[It’s important to keep talking about Maui] same way that people to this day still remember the Towers, to this day, how people remember Katrina. It needs to be remembered, because not only did we lose a part of our island, we lost a very historical part of the island.

Myriam:

We need to be following this situation because in my personal opinion, $700 doesn’t help these people. We need to keep talking about this because these people need help, the community needs help, Maui needs help. And this is a big part of our life, which means a lot; Maui means a lot for us. And Maui will recover, but there’s a long way, so that’s why we need to keep talking about this.

And on my part, I’ll just continue doing my shows, continue to make connections with different organizations for the community in general. I try to do my best and my part, [even if it’s just] 0.1%, whatever I can to help the community recover; to make it better for the people here in Maui.

Suzy:

I just want to say that for me, it’s important to continue talking about it because we need to learn our lessons. There had been some signs in the past that we were really facing danger of fire because of the grass and so something could have been done to avoid this.

And we need to be ready for the future and do what needs to be done. The fire burned Lahaina in less than 30 minutes. This was just something that we couldn’t even fathom.

What I’m doing personally now, being more on the TV side, is creating video segments, being mindful of the history that once existed, and I did a lot of segments about the history of those structures, but also the traditions. And I’m trying to avoid the present moment [and bringing] a little bit of hope into the future, in the way that I am living, by just trying to find a bridge between the past and the future, because right now, the present is kind of heavy.

But the present is made up of information coming from Honolulu Civil Beat [Hawaiʻi-based news organization that is this year’s Pulitzer Prize finalist in the Breaking News category], Akakū TV, the journalists and every member of the community that is contributing information through social media. So why it’s important: because we have to rely on the power of unity. And that’s what “Aloha” is supposed to be for.

All photos with exception of NASA photo used with permission of KAKU.