Since 1963, WPKN 89.5 (Bridgeport, Connecticut) has rocked, rattled and rolled the musical tastes and political perspectives of it listeners in three Connecticut counties—Fairfield, New Haven and Litchfield—and in Suffolk County on Long Island, New York. Broadcasting at 10,000 watts, the station serves a potential audience of 1.5 million.

Since 1963, WPKN 89.5 (Bridgeport, Connecticut) has rocked, rattled and rolled the musical tastes and political perspectives of it listeners in three Connecticut counties—Fairfield, New Haven and Litchfield—and in Suffolk County on Long Island, New York. Broadcasting at 10,000 watts, the station serves a potential audience of 1.5 million.

Always a champion of independent music, today’s DJs deliver programming in over a hundred genres—from rockabilly to twerk, blues to raga; from around the globe and across recorded time. Recently, the station broadcast selected live sets and interviews from Bridgeport’s Gathering of the Vibes, an annual festival of music sprung from the legacy of the Grateful Dead. Currently, the station’s website invites artists to submit imaginary album covers creating a visual playlist for “Sound and Vision,” a silent auction benefitting both the station and The Institute Library.

The station’s local, national and international public affairs programming, both locally-produced shows and those syndicated from Pacifica, has a long tradition of offering perspectives not otherwise or commonly represented in mainstream media.

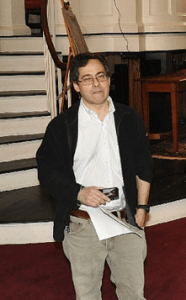

A program of local evening news is sourced by a station team. First Voices Indigenous Radio airs three times a month. The station’s weekly, live two-hour public affairs program Counterpoint and the syndicated Between the Lines, both produced by programmer Scott Harris, have been on the air for over 25 years. Harris says, “We started Between the Lines as the elder Bush was getting ready to launch the Gulf War in order to update people on the movements that were opposing the war and what was going on in the Middle East itself.”

“We’re a pretty special little station,” General Manager Steve di Costanzo says. “We’re proud of what we’ve been doing for over 50 years.”

“Everyone who comes into this station is an artist in their own right because they spend a tremendous amount of time thinking about what they want to play, how they want to play it.”

This enduring success comes, di Costanzo suggests, as a result of the station’s determination to grow with the times, to redefine and expand the concept of community engagement as both communities and technology change.

“The notion of community engagement is talked about a lot, but what does it mean in practice?” di Costanzo says. “We have consciously tried to understand that the two biggest challenges are to be relevant and to be visible, because, if you don’t have either of those two things, if we’re not relevant to our community or if we’re just an invisible station, we might as well pack it in.”

“Almost the entire success of our events can be attributed to the social networking that’s done.”

The impact of technological advances on listening habits is one of the key adaptations required of community radio. “I came in around 2007 or 2008, when the economy hit the skids,” Di Costanzo says. “Not only did some of the listener support start to wane, but technology was shifting the playing field. WPKN—and I’m sure a lot of other community radio stations that work free-form—was slow to catch up to trends in technology. For a long time stations like ours were incredibly relevant—the only place to hear unusual music, music from different countries and of different genres. Then suddenly you have streaming stations and satellite radio, and people who want to listen to bluegrass 24 hours a day for the rest of their lives can do that just by having a smart phone in their pocket.”

Di Costanzo says these changing circumstances required staff members to develop new approaches to community radio, approaches specifically focused on increasing relevance and visibility. “There was a pivotal moment of transformation necessary at that point.”

A first step in that transformation began with innovative programming. Di Costanzo recalls, “My predecessor, Peter Bochan, who came up from WBAI and was General Manager at the time, put together a community strip five days a week from noon until 1:00. It was all voices from the community, everything from organic farming to health and wellness to small business advice, arts and cultural shows. We made a real commitment to integrate into social and cultural organizations in our listening area, to give them a platform to be on air. ”

As representatives of local organizations were brought into the station, so station representatives stepped out and into their world.

“What we did even with our limited manpower—we’re all volunteers, about 130 volunteers, some part-time workers and one full-time employee, which would be me,” says di Costanzo, “We did everything we could to become media partners with local cultural organizations and performance spaces, so that we had some visibility presenting our logos at concerts or events.”

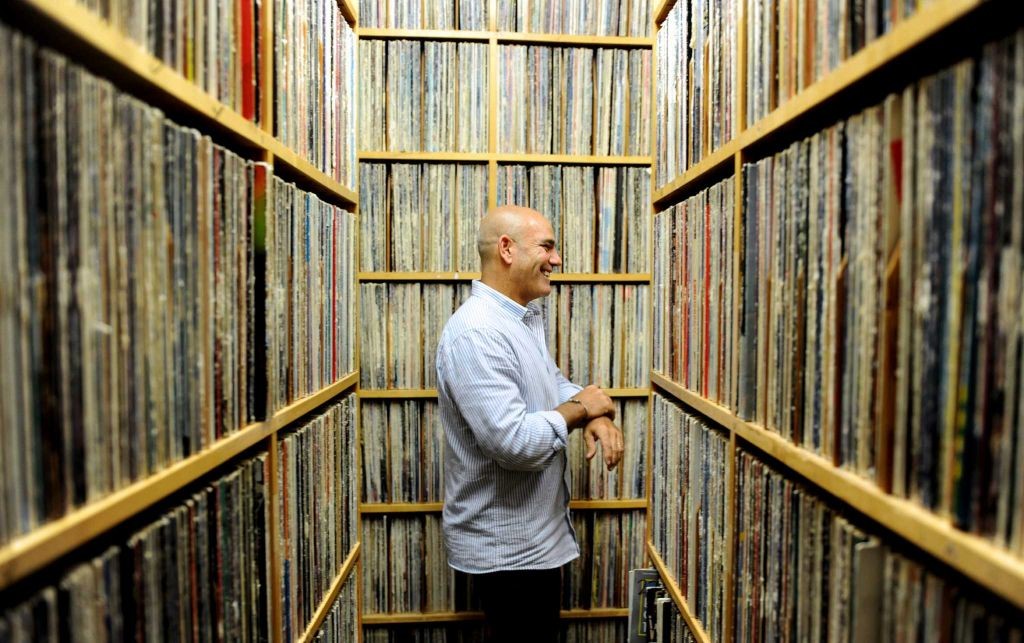

“We’ve been pretty pro-active in finding new voices. These younger programmers are really into vinyl. We have a huge collection, about 50,000 LPs. I talk about this sense of authenticity when you’ve got hands-on DJs, hands-on programmers, 24 hours a day.”

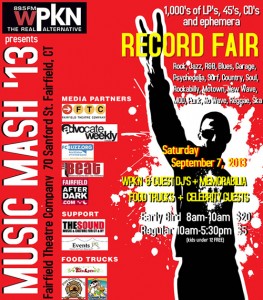

The station also began sponsoring its own events. “We did events that would be compelling for younger audiences and families. We created “Music Mash,” a large record fair with live music, food trucks and vendors from all over New England. We created a resurgence: being visible, fun, different, extending what we do as a community radio station right into the community and working with a lot of small mom-and-pop operations as sponsors.”

The station also began sponsoring its own events. “We did events that would be compelling for younger audiences and families. We created “Music Mash,” a large record fair with live music, food trucks and vendors from all over New England. We created a resurgence: being visible, fun, different, extending what we do as a community radio station right into the community and working with a lot of small mom-and-pop operations as sponsors.”

Younger listeners responded, and now, after some years of putting down roots, the station is benefitting both from this outreach and a renewed interest in vinyl among younger music fans. “We’ve been pretty pro-active—and this is kudos to our program director Valerie Richardson—[in] finding new voices. These younger programmers are really into vinyl. We have a huge collection, about 50,000 vinyl LPs. I talk about this sense of authenticity when you’ve got hands-on DJs, hands-on programmers, 24 hours a day. We do very little in the way of automation. We’ve added about fifteen new programmers.”

The station’s website is a rich source of both station and community information.

“We have a lot of links to community organizations, to festivals; it could be a Shakespeare event, a jam band festival. We have a very dedicated volunteer, one of those volunteers that, if an organization gets someone like him, it’s almost beyond good luck. He loves WPKN, so he actually works tremendously hard on the website.”

Syndication of locally-produced, award-winning public affairs programming has also expanded the station’s audience. Counterpoint, which first aired in 1987 and still anchors the station’s Monday evening program, expanded to become the syndicated Between the Lines in 1991. BtL currently airs on over 60 stations.

“We’re picking up new stations all the time,” says producer Scott Harris. “Many new low-power stations created through the FCC licensing process are looking for programs like ours. We’re tapping into a whole new community.”

BtL also sponsors a series of community forums on issues from health care to civil liberties, to war and peace. “There has always been an encouraging turnout. People are passionate about supporting the station,” says Harris. “Meeting folks at community forums is a real jolt of energy and encouragement.”

Effective utilization of social media, particularly Facebook and Instagram, also contributes to the station’s success. The station has its own app for Android and Apple.

Di Costanzo says, “Almost the entire success of our events can be attributed to the social networking that’s done. We know that the next generation of listeners is plugging into smart phones and streaming.”

“We have consciously tried to understand that the two biggest challenges are to be relevant and to be visible…if you don’t have either of those two things, we might as well pack it in.”

The station’s next technological endeavor will be to develop podcasts of their extensive public affairs programming. “That’s pivotally important for us,” says di Costanzo. “We did some 600 public affairs-related episodes last year. They are in the archives but are not downloadable. For us, that would be another way of being more relevant or more visible.”

More and more, di Costanzo conceives of the station as an arts organization. “Our medium happens to be radio and music and public affairs. But everyone who comes into this station is an artist in their own right because they spend a tremendous amount of time thinking about what they want to play, how they want to play it.“

This shifting focus, di Costanzo believes, will also help with funding. “When I look at grants, I never find ‘non-profit radio station’ on a pull-down menu of any state or national organizations. When I approach community foundations—we’re a fifty year community radio station doing tremendous things in the community—their response is that they don’t have a track record of giving to non-profit radio stations.”

The station has also begun to accept underwriting. “We try to find some like-minded sponsors. We’ve found we work pretty nicely with smaller mom-and-pop type of companies that have some aligned thinking with the ethos of WPKN.”

“We were pretty disappointed to lose a recent $64,000 [Corporation for Public Broadcasting] community service grant,” di Costanzo adds. “A particular metric showed either that we were underperforming or we have a lot of upside for contributions. That’s the catch-22. We applied in the first place because we desperately need to raise outside money to get more listeners. It’s hard when you have no money for marketing or advertising.”

In the end, all of this work comes back to strengthening the beating heart of the endeavor, WPKN, the station. Di Costanzo says, “When I came in, I had no background in radio. But I loved the station and bought into its mission because we fill in something incredible in the community and in the listeners.”

Harris, reflecting on his long-time connection to the station, first as young listener and now as long-time programmer, says, “There were some older programmers who began a tradition when WPKN started who helped me to understand politics from a different point of view. I got a great political education through the station. Now, I continue the tradition. This is a continuum, carrying on a legacy.”

Harris, reflecting on his long-time connection to the station, first as young listener and now as long-time programmer, says, “There were some older programmers who began a tradition when WPKN started who helped me to understand politics from a different point of view. I got a great political education through the station. Now, I continue the tradition. This is a continuum, carrying on a legacy.”

And, Harris adds, “That’s the beauty of community radio. It’s not market researched; it’s not targeting one particular demographic in some scientific way that closes off a lot of other possibilities. There’s experimentation and chances being taken that engage an audience. It’s an important platform to keep alive. Just keep the radio on and see what comes next.”