The months after November’s presidential election have been filled with conspiracy theories, lies and myths about the security and integrity of U.S. elections, led by former President Donald Trump and many Republican leaders.

As a result, polls show that more than half of Republican voters wrongly believe that President Joe Biden and his supporters engaged in fraud to steal the election—a view backed by most congressional Republicans and scores of state and local GOP officials.

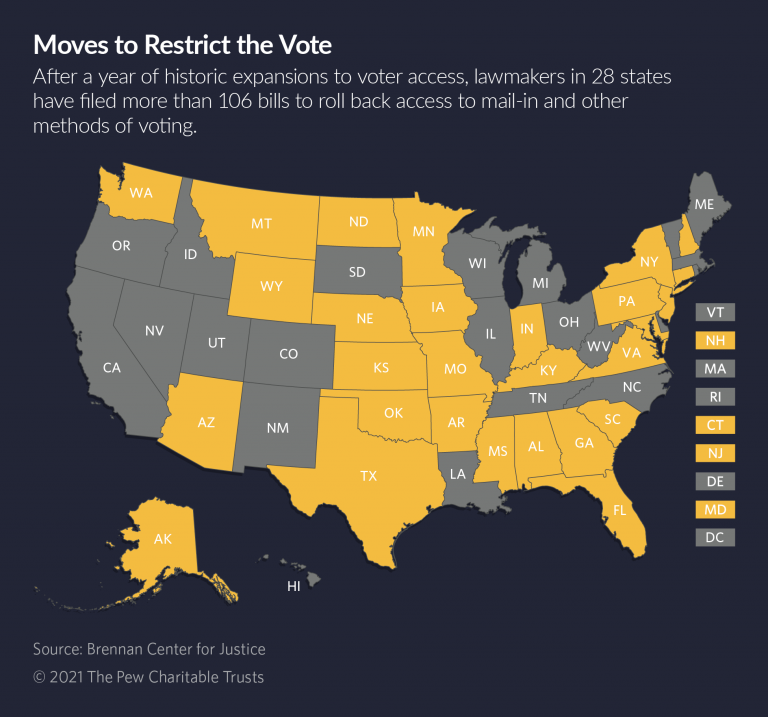

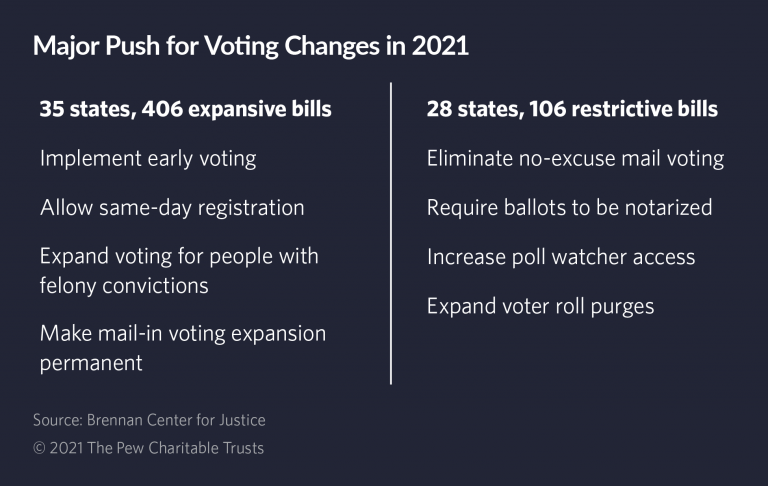

Pointing to their constituents’ doubts, GOP lawmakers in at least 28 states have introduced more than 100 bills to tighten voting rules, according to a recent report from the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law. The bills would, for example, add new voter registration requirements and scale back or eliminate voting by mail, which voters flocked to during the pandemic. Supporters say these measures would restore public confidence in elections.

Republicans have for the past two decades worked to restrict voter access, instituting voter ID laws, shortening early voting periods and purging inactive voters from registration rolls. Often, state lawmakers said these measures were necessary to prevent widespread voter fraud, despite a lack of evidence. Now, many Republican lawmakers cite a new reason for restrictive laws: the lack of voter confidence in the integrity of U.S. elections, which Trump has fomented since he entered politics.

Some of these bills would add photo ID requirements for mail-in ballots, ban ballot drop boxes and eliminate the option to vote by mail for most voters. Others would require witness or notary signatures for mail-in ballots and eliminate automatic voter registration.

Several are being pushed in states that Biden narrowly won, such as Arizona, Georgia and Pennsylvania. All three have Republican-dominated legislatures, and saw record turnout in 2020 as many voters used mail-in voting to safely cast their ballots in the middle of a pandemic.

Voting rights advocates and Democratic lawmakers argue this flood of new legislation springs from debunked theories of widespread voter fraud and lies about a stolen election, and is designed to disenfranchise Democratic-leaning voters.

“You can draw a pretty straight line between the baseless and racist accusations of voter fraud and the kinds of bills we’re seeing introduced,” said Hannah Klain, a Brennan Center fellow and one of the report’s authors. Many of Republicans’ fraud claims have focused on cities with large communities of color.

Republicans who have introduced these bills say their primary motivation is to ensure elections are run securely and efficiently.

“This is about good governance. It’s not disenfranchising anybody,” said Arizona state Sen. Michelle Ugenti-Rita, a Republican who is sponsoring a dozen election-related bills this session.

One of her proposed measures would remove voters who don’t participate in two consecutive election cycles from the state’s permanent early voting list; they would remain registered voters but would no longer automatically receive a mail-in ballot.

Other Republican legislators say these restrictive measures are necessary to prevent voter fraud, which election experts maintain is vanishingly rare. Top election officials in the U.S. said in November that the election was “the most secure in American history.”

“It’s frustrating to see laws put in place to restrict access in the name of solving a problem that doesn’t exist,” Klain said.

Restrictions aren’t the only changes on the horizon. There are far more bills this legislative session that would expand voter access. Lawmakers in 35 states have introduced more than 400 bills that would allow all voters to cast their ballots by mail, authorize drop boxes and set up processes to fix mail-in ballots with technical errors, according to the Brennan Center report. Other proposed bills would expand early voting periods, allow for same-day voter registration and restore voting rights to those with past felony convictions.

While voting rights advocates are encouraged by the volume of bills that would expand access to the ballot, they remain concerned about the restrictive measures moving through state legislatures. If passed, these measures could reverse some of the biggest expansions made to voting in decades, which were the scaffolding for last year’s historic turnout levels.

Rolling Back Voting Access

In Georgia, Republicans want to dismantle many of the expansive voting policies that led to historic turnout in 2020—the highest ever recorded in Georgia in a presidential election. Biden put the state into the Democratic column for the first time since 1992, and Democrats Rafael Warnock and Jon Ossoff won surprising victories in last month’s runoff elections for the U.S. Senate.

Republican lawmakers in the Peach State have introduced legislation that would ban drop boxes, automatic voter registration and no-excuse absentee voting. Another bill would require voters to submit a photo ID both when they apply to vote by mail and when they submit their ballot.

The author of the voter ID legislation, Republican state Sen. Jason Anavitarte, did not respond to several requests for comment. Senate President Pro Tempore Butch Miller told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that these measures would “restore confidence in the ballot box.”

Voting rights advocates in the state say these measures would do the opposite, making it more difficult to cast a ballot. It’s voter suppression, said Helen Butler, the executive director of the Georgia Coalition for the Peoples’ Agenda, an Atlanta-based nonprofit that advocates for voting rights.

“We demand full, fair access to the ballot,” she said. “This historic turnout cannot be clouded by false and misleading narratives and claims of voter fraud.”

Rick Barron, the nonpartisan elections director of Fulton County, which includes Atlanta and a large portion of the state’s electorate, said expansive voting policies, such as mail-in voting, have been invaluable to the success of recent elections, especially during a pandemic.

“I just don’t want to see any rollbacks in Georgia,” he said. “As an elections administrator, absentee by mail makes the entire process smoother.”

Pennsylvania, another state that expanded voter access before the pandemic, also may reverse course. State lawmakers have introduced at least 14 restrictive voting measures, including some that would require a state-approved excuse to vote absentee. A group of state lawmakers and election officials are separately working on an advisory board, established in March 2020, that is examining the state’s election laws.

In Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has said tightening election rules will be one of his top priorities this year, despite the Lone Star State having some of the most restrictive voting policies in the country. Republicans there have introduced at least eight bills that would narrow access.

“You can draw a pretty straight line between the baseless and racist accusations of voter fraud and the kinds of bills we’re seeing introduced.”

Hannah Klain, fellow, Brennan Center for Justice

Elsewhere, bills that would purge inactive voters from rolls are advancing in Mississippi and five other states. Montana Republicans are moving forward with a proposal to end same-day voter registration, joining Republicans in Connecticut, New Hampshire and Virginia pursuing similar efforts.

In New Hampshire, Republican state Sen. Bob Giuda introduced legislation that would require voters to submit a photo ID for both an absentee ballot application and the ballot itself. He said the bill is a reasonable and practical attempt at ensuring that only eligible voters participate in elections.

“Our goal is not to be exclusive, but inclusive,” he said. “You have the right to vote absentee. But we want to know it’s you.”

Democratic state Sen. Rebecca Perkins Kwoka said the Granite State has not had a voter fraud problem. She worries this bill would limit access for rural and older voters who may not have access to scanners.

“While we all like to believe these voters have help or someone to assist them with their ballots, that’s just not the reality,” she said. Perkins Kwoka has introduced legislation that would allow anyone to vote absentee without an excuse.

Giuda listened to some of these criticisms and will amend his bill to allow people to write their driver’s license number or the name and address of their landlord on the inner envelope of their mail-in ballot to confirm their identification.

A ‘Confidence’ Crisis

The public’s confidence in elections is shaken, said Alaska state Sen. Mike Shower, a Republican leading an effort to reshape the state’s mail-in voting system.

Like many other voters across the country, Alaskans leaned heavily on early voting during the pandemic, buoyed by a state Supreme Court decision that threw out a requirement for a witness signature on absentee ballots.

But Shower said many of his constituents are upset about an election they feel was illegitimate. Only a third of Republicans nationally trust U.S. elections, according to several recent polls.

He introduced legislation this session that would, among other things, prohibit cities from mailing ballots to every registered voter and stop automatically registering people to vote when they apply for the state’s Permanent Fund dividend, an annual payment to Alaskans drawn from state oil revenues. The bill also would ban “ballot harvesting,” where groups collect absentee ballots for people who may be unable to mail or physically turn in their ballots. These measures, he said, would restore confidence in the state’s election system.

“Local jurisdictions flood the mail with ballots with no chain of custody protocols,” he said in an email statement. “There are many opportunities for error, or fraud, to be introduced into the system.”

Indigenous groups are concerned the bill would disproportionately affect their communities, many of which skew older, are located in rural areas and sometimes enlist nonprofits to collect their ballots. This year, for example, Native Peoples Action, an Indigenous-led nonprofit based in Alaska, hired 15 voter engagement specialists across the state to help voters cast their ballots. Group leaders worry this may become illegal if the bill passes.

“Their whole excuse is voter fraud, but they can’t pinpoint it,” said Kendra Kloster, the group’s executive director. “There are no examples of it. They’re trying to pass legislation when there’s no problem.”

Democratic state Sen. Scott Kawasaki, who sits on the committee considering this legislation, said the bill could disenfranchise voters throughout the state.

“It’s really part of this narrative that the election was stolen,” he said. “This is clear, plain and simple, voter suppression.”

In Arizona, restoring confidence, efficiency and security in elections is at the heart of Ugenti-Rita’s legislation, she said. The Scottsdale Republican said there is a crisis of confidence in elections, especially around mail-in voting. Fundamentally, she does not have a problem with voting by mail—she does it herself. Her measures, she said, would “reinforce” the system.

“You have big problems if the public starts to doubt the results of the election, for whatever reason, whether merit-based or not,” she said. “They could do significant damage.”

Conspiracy theories that Trump and many Republican leaders spread after November’s election are to blame for this public misconception, said Arizona state Sen. Athena Salman, the Democratic whip.

“Since their attempted coup and insurrection failed, they’re on to Plan B,” she said. “This is an assault on our democracy. This is being waged by a political party that didn’t like the way voters chose and want to take the vote from you.”

Other Republican-sponsored legislation in Arizona would do away entirely with the permanent early voting list, give the state legislature the ability to overturn presidential election results and require a notary signature on early ballots. Notary signatures are required in other states, such as Mississippi, Missouri and Oklahoma.

Leslie Hoffman, the Yavapai County recorder, has been lobbying against some of these measures she said would harm a voting system that works for the state.

“Some of our friends in Arizona are looking backwards,” she said, “and trying to reverse our really good policies.”

Matt Vasilogambro is a reporter for Stateline.org, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts, where this story first appeared.